RETURN TO ARTICLE LIST

Sideboarding 101

Written by Noel

Created 12 July, 2025

Last updated 14 July, 2025

A few months ago I traveled to the Netherlands to play in Ascent Utrecht, and while sitting down for Round 1, the player next to me called over a judge to ask a perfectly innocent question: “Hey judge, I have this printed out sideboard guide. Am I allowed to reference it between games?” While this is allowed in some other TCGs, such as Magic: the Gathering, in Grand Archive it is not:

Similarly, one of the most common questions I get about any deck I’ve played is “what do you sideboard for X matchup?” While this seems like a reasonable question, both are indicative of a critical skill that is missing for many players: how to sideboard. I don't mean simply the decision of picking what cards to bring in and take out; what many players don’t realize when looking at tournament topping lists online is that those sideboards are heavily tailored not only to that exact list, but that event itself. Therefore, understanding how to build a sideboard for a deck in the first place is a crucial skill.

Function of the Sideboard

Fundamentally, it’s so that you can tailor your deck to the one that your opponent is playing. By swapping out cards that aren’t very useful against your opponent’s deck for cards that are, you can have a much better game 2 and 3, leading to more engaging matches and a better play experience. Now, does this have a higher impact on your good matchups, or your bad matchups? It should have a higher impact on your losing matchups. If you’re already favored, then making your deck even more favored isn’t doing very much. But if you’re unfavored, then bringing in cards that are good against your opponent can have a very high impact. For example, let’s say I’m playing a deck like Arcane Rai that loses pretty badly to ally rush strategies. If I sideboard in cards like Resolute Stand and Vanish From Sight, I can drastically increase my odds of winning.

If the sideboard didn’t exist, how would a deck accommodate its bad matchups? If you just took most decklists and didn’t change them outside of removing their sideboards, then there would be a lot of very polarized matches, and winning matches in a tournament would be dependent on pairing RNG. Realistically though, this would be mitigated by playing cards in the maindeck that are typically ‘sideboard cards’ (cards specifically meant to counter specific strategies). The Rai deck would likely maindeck the Resolute Stands, and maybe even the Vanish From Sights. Even though these cards aren’t good into most matchups, they are required for your bad matchups, so the deckbuilder might decide that it is worthwhile to have these “sometimes great, sometimes dead” cards.

The sideboard allows decks to play a more streamlined main deck, and relegate these matchup dependent cards to the sideboard. This leads to more consistent game 1s, with cards that are more often “live,” and it is the strategy that many players employ when building their decks. Now, if we had unlimited sideboard space, then every deck could just sideboard all the good cards against every other deck. Alas, we are only allowed 15 slots, so as deckbuilders and players, we need to be judicious in deciding what makes the cut. If I’m playing allies, do I really want to sideboard Incapacitate to make my already good Rai matchup even better? Or would I rather sideboard cards for more challenging matchups?

What to Include in Your Sideboard

Due to limited space, we must carefully consider the cards that we want to put into our sideboard. There are 3 primary ‘rules’ (more like guidelines) that I like to follow when building my sideboards:

Sideboard cards for your bad matchups

Sideboard generic cards to cover all matchups

Sideboard for the expected meta

I mentioned the first rule above as one of the primary functions of the sideboard, covering your bad matchups. This strategy is quite effective for decks with some very polarized matchups that have effective ‘silver bullets,’ cards that are extremely powerful against a particular deck/strategy.

A good example of this in a modern competitive setting is Caban’s winning Fractal list from OCE Nationals. Since the deck already had a very powerful matchup spread, TCG was comfortable dedicating 6 out of their 15 slots specifically to Wind Allies, a tight matchup that was a popular deck in OCE.

By siding out Quicksilver Grail for Art of War, and Turbo Charge, Captivating Opulence, and a Fractal of Intrusion for 3 Chill to the Bone, TCG’s list pivoted to being an extremely potent control deck in that matchup specifically; Art of War slows the ally player down drastically, giving Fractals time to effectively trade removal spells 1 for 1 with the opposing allies, and taking over the long game through the card advantage from Lost in Thought and Zhang Jiao. With this sideboard plan, TCG felt that they didn’t really have any bad matchups for the event, and their confidence was validated with Caban’s win and Terry’s 10th place finish.

Sometimes, you can take this strategy to some crazy extremes; let’s look at the Serene Luxem deck that Chess Club brought to NA Nationals 2024. Similarly to fractals, Luxem had a pretty incredible matchup spread into most of the popular decks at the time; however, it had 2 really bad matchups: Erupting and TaserLock / Fire Diana. Nullifying Lantern was a useful hate card for Erupting, but it could be easily removed by Spurn to Ash. We thought about playing Water Luxem so that we could Fracturize the Lantern, making it a phantasia that also keeps its primary ability due to a quirky rules interaction (Layers). This would prevent Spurn to Ash from destroying the Lantern, and the Fracturize would also be very effective into TaserLock by removing their Shadow’s Twin before they could shoot us. However, the problem is that Water Luxem was a lot worse into the majority of the field. So, what was our solution? Both. Both is good.

Since our deck had a very low fire count, we realized that we could simply sideboard Spirit of Serene Water and 4 Fracturize, and swap elements post sideboard. We could reliably win games 2 and 3 of our bad matchups on the back of Fracturize alone, allowing us to keep a much more consistent main deck. While we didn’t have space to sideboard for the broader field, we were confident in the power of our main deck to not need any additional help. This strategy proved effective, landing most of the team into Day 2 and Burner a Top 4 finish, qualifying him for Worlds.

The second rule is more something to keep in mind when you take a step back and evaluate your sideboard, and something I always keep in the back of my mind. If two cards are similarly effective vs a bad matchup, but one is more generic for other matchups, then I’ll usually pick the more generic option. This is because you want to avoid having ‘dead’ cards in as many matchups as possible, so cards that are effective across multiple matchups are incredibly useful. A variation on this is to primarily sideboard extremely targeted cards for specific matchups, and a handful of more generic cards that advance your primary gameplan rather than focus on your opponent. Then if you pair into a deck that your sideboard tools aren’t well suited for, you can side out any ineffective interaction pieces in your main deck for the proactive cards in your side deck.

The third rule is most effective in a tournament setting midway through a format, when there is an established metagame and you can reliably expect to play into a specific few decks. Rather than prepare for a broad field, you can sideboard specifically for those few decks that you expect to play against. No need to bother sideboarding for your bad matchup if you likely won’t play vs it, so why not play the cards that are very good vs the decks you’ll likely play into? You might turn a favorable matchup into a very favored matchup, leading to good odds of an effective tournament run.

This strategy can also be effective at a local setting, where the players often play the same decks week to week. Always struggle into that 1 really good Fire Merlin player at your locals, even though it should be a good matchup? Throw some regalia destruction in to prevent them from resolving their Ghosts of Pendragon to draw cards or loop their Prismatic Edge with Sword of Ascension. Struggling once they land a Majestic Spirit? Put in Immolation Trap or Dream Fairy to quickly remove it, or an Incapacitate to negate the Incarnate Majesty itself! Is that Slime player a real pain? Add some Dusklight Communions and an Umbra card to prevent them from reaching the Pride 3 threshold. Wind Tristan? Sideboard Staggering Strike. Fractals? Phantasia destruction cards.

Bringing the Rules Together

Ideally, you want to use all 3 guidelines in tandem with each other when preparing for a major event. Let’s take a look at the Water Merlin deck that I brought to Ascent Utrecht:

Starting with a rule 1, my bad matchups; Slimes and Aggro. For Slimes, I decided to bring Dusklight Communions as targeted hate. It allows you to slow down the game to get to your Majestic Spirit, and we have Fracturize in the maindeck to remove their Beastbond Ears. For aggro, I made a bit of a gamble by employing rule 3; figuring that I was unlikely to play into them, I didn’t sideboard any cards to improve the aggro matchup (such as Resolute Stand).

Continuing with rule 3, the expected meta had a lot of Water Mill decks, and losing to deckout was a genuine fear if they were able to remove our Nullifying Lantern, so I wanted some phantasia removal to deal with any early Fractal of Polar Depths. Phantasia removal would also be useful against the random Razorgale decks, and killing a Fractal of Rain wouldn’t be the worst either. Versus Astra, removing a Fertile Grounds denies them 4 or more cards over the course of the game, which is incredibly effective. I could have chosen Mystic Purifier, but instead chose an astra card and doubled up on Dusklight Communion’s effectiveness. The main idea here was that purifier simply cost too much; you couldn’t play it and another spell in the same turn, and it could be easily negated with Frozen Dismissal or a Stifling Trap. And since I didn’t value being able to resolve multiple destruction effects in the same game, there wasn’t a big downside to Dusklight. Next, Song of Frost was additional targeted hate card for all these Icebound Slam decks, and also is a nail in the coffin card vs Nico to negate their Ravishing Finales.

Lastly, I used the variation of the 2nd rule to round out my sideboard by playing 3 generically useful cards for my primary gameplan (Mind Freeze, Harmonious Mantra, and Sudden Steel), which I could use to tweak my interaction package based on what I was playing versus.

The sideboard worked out great; I finished the Ascent in 3rd place, winning a Gwendolyn, Spirit of Wind.

What to Sideboard In and Out?

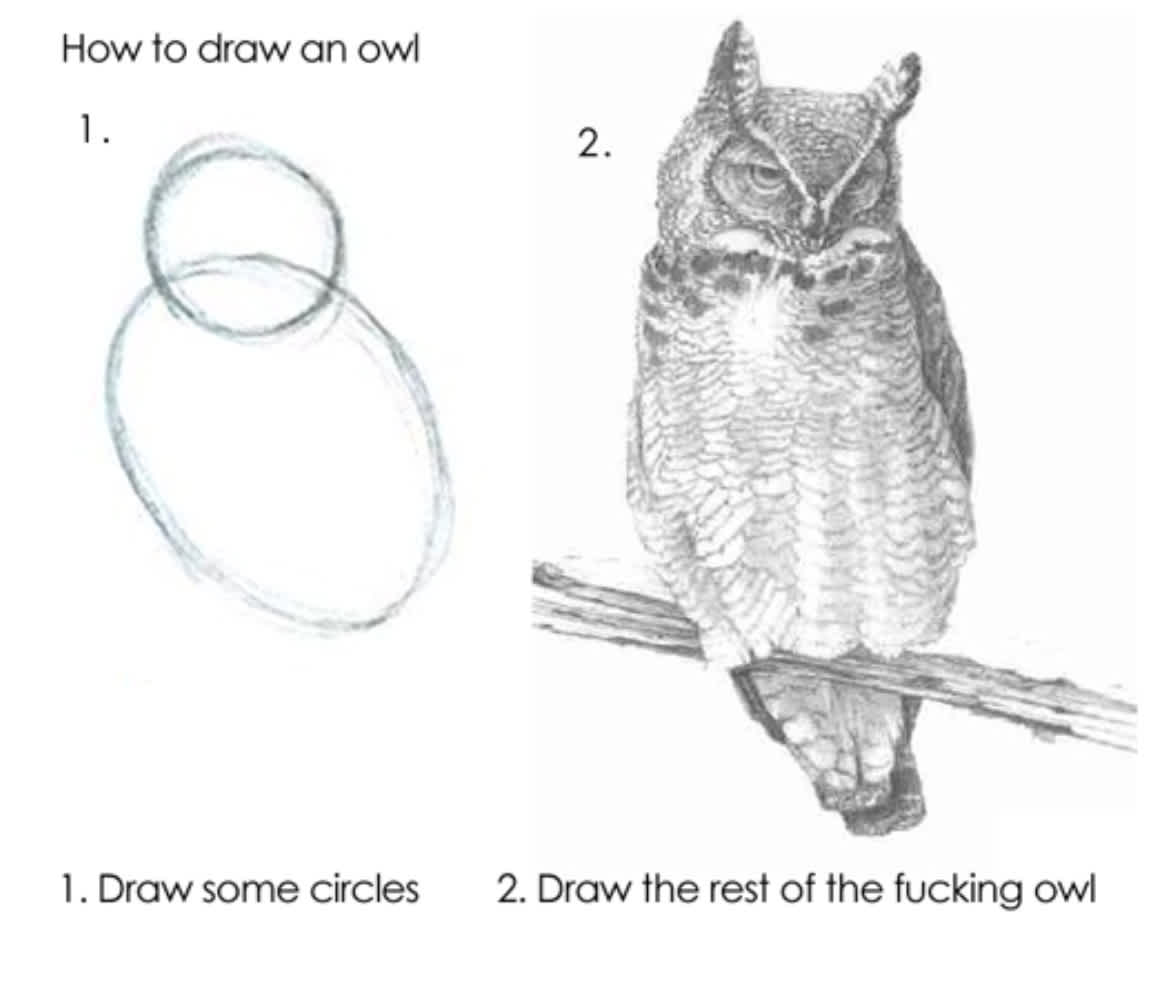

Now that we’ve covered the high level thinking of the purpose of our sideboard, and a deckbuilding approach of what you want to include in your sideboard, we can cover a key takeaway from this article: “what do you sideboard for X matchup?” Honestly, the answer is actually very simple: “Take out the bad cards and put in the good cards.”

This might sound like a “draw the rest of the owl” situation, but I’m serious, that’s legitimately all there is to it. First, identify what cards are bad / ineffective in the matchup you’re playing, and take them out. Now take an equal number of cards from your sideboard that are effective in the matchup and put them in. This is why I spent most of the article talking about how to actually build a sideboard, because it gets you thinking about the role of the sideboard as part of the decklist as a whole; if you look at a tournament topping list and don’t understand why X card is in the sideboard, take a step back and look at the list as a whole, then at X card. Ask what role that card fills, and how is that role relevant to the deck. Once you understand the deck and the role of the cards in it (both in the main deck and side deck), sideboarding becomes as easy as “Take out the bad cards and put in the good cards.”

Oversiding

A very common mistake players make is “oversiding” for a matchup, where they really want to beat X matchup and side in 6, 7, maybe 8 cards for it. But when they look at their main deck, they only have 3-4 cards that they actually want to take out, and are faced with figuring out which core or engine cards they want to side out for the extra tech. This often leads to having an weaker deck post sideboard, and losing the match despite all of the sideboard hate. Going back to the deckbuilding approach, when building your sideboard think ahead about what matchups you’re siding for, and what cards you want to take out. You could easily say that you only have 1 bad matchup and you want to side 15 cards for it, but I can promise you that for 9 out of 10 decks, siding out 15 cards will absolutely cripple your core gameplan. Instead, pick the number of cards you can side out without hurting your deck’s gameplan, probably 3-5, and then pick the 3-5 most effective cards to bring in for the matchup. Now go to the next matchup and repeat. As a bonus, by doing it this way you’ll also develop your own sideboard guide, and when you go to sideboard you won’t even need to think about what cards are good or bad for the matchup, you just already know what to swap.

Another way to look at it is to shuffle your entire sideboard into your main deck, and then take out the worst 15 cards for that matchup. This can be pretty effective if you’ve just picked up a deck from someone else, maybe a list that performed at a recent tournament, and it’ll help you practice that deckbuilding philosophy. The people who built that deck probably built the sideboard methodically, with a specific purpose for each card, so challenge yourself to figure out what it is. This will lead to being a better player and deckbuilder, and you might even find ways to improve upon the deck. Bonus tip, siding in 15 cards then taking out 15 cards is a real pro strategy for tournament play called Smokescreening, since it prevents your opponent from seeing how many cards you sided in for the matchup.

Something to remember is that the sideboard for those decklists isn’t set in stone either, but should instead be seen as pretty fluid. Proper sideboards should be tailored for a specific event, but even then, “no good plan survives contact with the enemy.” Take the Water Merlin deck above; the sideboard plan felt very good in theory and in testing, but in practice the phantasia removal wasn’t actually that good into the Slam decks since there wasn’t a good way to bring in the Astra card, which was a gap in our deckbuilding that we hadn’t considered.

Ultimately, sideboarding is an exercise in deckbuilding, and taking the time to understand the “why” behind the sideboard and how it compliments the maindeck will lead to a better understanding of the deck and its matchups as a whole. So next time you catch yourself looking at a decklist and going “how do you sideboard with this deck,” challenge yourself with it a bit; identify which cards are bad in the matchup, which cards are useful, and if there’s a clean swap.